Discovering the Fabulists: The Value of the Bizarre in Literature

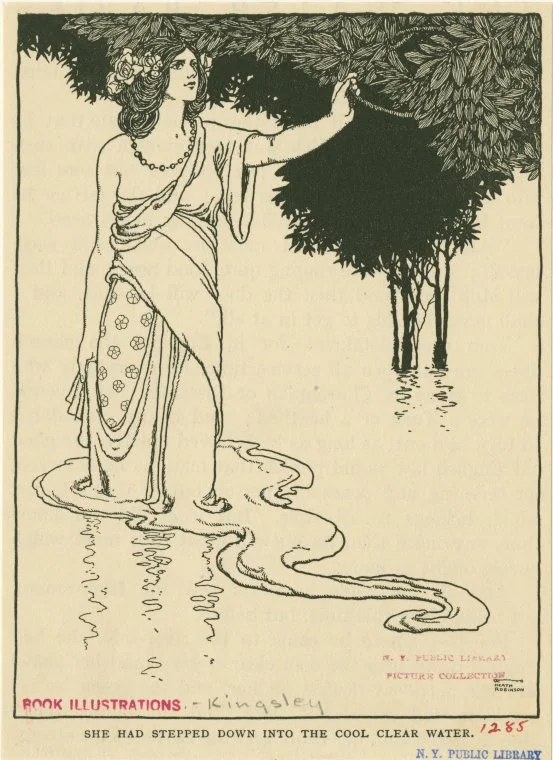

Image Credit: New York Public Library

After workshopping a piece of my fiction last year, a classmate told me encouragingly that I might be writing in the fabulist tradition. She directed me toward the Tin House collection, Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime, and I do not say this lightly—everything changed.

Inside were 18 stories by now dear-to-me authors Kelly Link, Julia Elliott, Karen Russell, Samantha Hunt, Alissa Nutting, and Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum, to name a few. Who were these women, I thought, these so-called fabulists? They were so brash in their writing about a nightly transformation into a deer, about growing up next door to a pack of wild boys, about joining the mermaids (and your mother) under the sea. How had I survived so long in the dreary world of American literary fiction without these magical, mythical, beautiful stories? I immediately tore into forerunners Angela Carter and Shirley Jackson, I delved into the impeccable Carmen Maria Machado, whose collection of short stories includes a retelling of the girl with the green ribbon. I couldn’t get enough of the vivid colors, the blood and heartache, the natural world. Like these stories, I too wanted to look directly into a dozen curious wounds, eager to lick up every drop.

"We didn't speak, and a beautiful, sweet evil grew between us." — Julia Elliott, The Wilds

Image Credit New York Public Library

"Fabulism, often interchangeable with magical realism...incorporates fantastical elements within a realistic setting ," author Amber Sparks wrote in Electric Literature. "These fantastical elements are often cribbed from myth, fairy tale or folk tale. Strange things happen and characters react by shrugging: animals talk, people fly, the dead get up and walk around. Time operates sideways, nature behaves mysteriously.”

I started pushing back in my own writing and in my own literary tastes. Insects started to crawl off the page, I left letters in open chest cavities, a foot washed up on the shore. Why couldn’t a story exist in the real world and take a well-placed dip into the fantastic, into the fabulous? Why couldn’t our stories be told in this dimension and the next, borrowing from folk tales, science fiction, fantasy, or horror? What did realism have that other genres didn't have, and who was to say that realism was the only literary form of fiction?

"As far as Mother understands, hers is not the only family ever to experience calamity. Daughters wander off into the woods, stumble into prostitution, fall in love with sailors, are eaten by wolves." — Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum, Madeline Is Sleeping

In the words of the late literary giant Ursula K. Le Guin, the problem is "the maintenance of an arbitrary division between 'literature' and 'genre,' the refusal to admit that every piece of fiction belongs to a genre, or several genres."

We live in a world where the unreal happens every day: devices bring universes into our homes, governments rise and topple, monsters hide in our offices and schools, reality television stars win presidencies, and humans are born and die, every second. Our lives are bizarre, meandering, and fantastic. Shouldn’t our fiction reflect that?

"The mermaids were an invasive species, like the iguanas. People had brought them back from one of the Disney pocket universes, as pets, and now they were everywhere, small but numerous in a way that appealed to children and bird-watchers." — Kelly Link, Light

While discovering the immense wealth of stories daring to push into the bizarre and surreal (including some amazing work—read this whole list of African science fiction, and this Swiss gothic horror translation, and The End of Days by German author Jenny Erpenbeck, a life told in five deaths), I am continually floored. I spent years struggling to convince myself that folk tales and the fantastic could also be literary. A difficult lesson to learn, but it's an important one the fabulists taught me.

"This time I try to be honest with him. I say it. 'I mean I think I'm becoming a deer.'

'You think you're becoming a deer?' he asks." — Samantha Hunt, Beast

When we relegate certain types of work into literary or non-literary, we undermine the purpose of fiction: to reflect our humanity and our reality, both of which are strange and fantastic in their purest forms. These writers exist, these stories exist. The strange and fabulous exists.

—Hannah Gilham

Co-Web Editor